Encyclopedia Witchcraft Demonology Robbins Pdf Writer

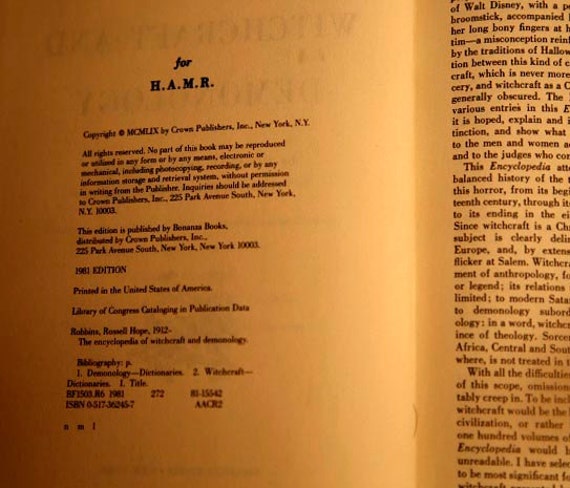

The world of scholarship has been eagerly awaiting this ambitious encyclopedia for several years. Its most comprehensive predecessor has long been The Encyclopedia of Witchcraft and Demonology (1959, with 227 entries), by the medieval English literary scholar Rossell Hope Robbins. Recent smaller entries into this field have not been an adequate substitute for a thorough reassessment of the state of this burgeoning area of historical research. Robbins’s work summarized much of what was known and thought before scholars began their systematic assault upon the archival records of witchcraft trials, and so it is not surprising that his entries on many individual demonologists have stood the test of time better than his attempts to survey the history of [End Page 87] actual witchcraft trials. In fact, Richard Golden’s four volumes with 758 entries, co-edited by six other prominent scholars and written by an international team of 170 experts (29% of them women) from 29 countries, combine such a wealth of knowledge from so many countries and cover so many aspects of the history of witchcraft, that they can serve as a means to assess the health, progress, and maturity of various subfields. In this review I will confine myself to the main emphases of the editors and of the authors they recruited. One should note at the outset that although the subtitle of the Encyclopedia is “The Western Tradition,” the vast majority of articles deal with European witchcraft between the years 1400 and 1750, that is, the years of the so-called great European witch hunt.

A dozen learned articles treat ancient Greek and Roman witchcraft (e.g., “Homer,” “Medea,” “Greek Magical Papyri,” “Horace,” “ Defixiones,” “Laws on Witchcraft—Ancient,” “Apuleius of Madaura”), and there are a few essential entries on the Bible (e.g., “Bible,” “Moses,” “Exodus 22:18,” “the witch of Endor”). Similarly, key medieval thinkers (e.g., Gratian, John of Salisbury, Thomas Aquinas, Pope John XXII) and key medieval documents (e.g., the Canon Episcopi, “Laws on Witchcraft—Medieval”) attract a small bouquet of usefully learned articles. But these entries pale in comparison with the huge number of often overlapping articles treating the late Middle Ages and the early modern period.

The Encyclopedia of Witchcraft & Demonology has 309 ratings and 19 reviews. Elizabeth said: Just a neat book I picked up back in the 80s after studying C. Gfp-001 Windows 7 Driver on this page. The Encyclopedia of Witchcraft and Demonology by Russel Hope Robbins. It focuses on witch hunts and Christian-based deviltry, rather than the wider questions of esoteric thought. They didn't write back-which I remember thinking was shit- but saw it in Whitcouls a year or so later and got it.

The reason is not far to seek. Mechwarrior 4 Vengeance Isotonic. The fundamental subject of Golden’s Encyclopedia is not so much the broad topic of witchcraft, demonology, or magic (as a belief or a practice) but the escalating series of witchcraft prosecutions that plagued much of Europe in the three centuries after 1420.

So overwhelming is the emphasis on witchcraft trials that one can say that these volumes are now not only the single best place to begin the study of European witchcraft but actually also the best introduction to the comparative history of early modern European criminal procedure.

From 'The Encyclopedia of Witchcraft and Demonology' by Robbins / Crown / 1959 BIBLE WITCHCRAFT. One of histories ironies is the justification of witchcraft on biblical texts, written originally for a religion which had no devil. Catholics and Protestants quoted Exodus xxii. 18, 'Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live.' But the Hebrew word kaskagh (occuring twelve times in the Old Testament with various meanings) here means, as Reginald Scot pointed out in 1584, 'poisoner,' and certainly had nothing to do with the highly sophisticated Christian conception of a witch.

Yet the domination of Holy Scriptures was such that these mistranslations fostered the delusion. After the execution of Goody Knapp at Fairfield (Kent) in 1653, a neighbor said 'it was long before she could believe this poor woman was a witch, or that there were any witches, till the word of God convinced her, which saith, Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live.' Another text which changed the Hebrew meaning--'a woman with a familiar spirit' for 'pythoness'-- occurred in 1 Samuel xxvii, the miscalled Witch of Endor. Writers who tried to expose the witchcraft superstition, such as Reginald Scot or Thomas Ady, had to clear up two fallacies: (1) The numerous Hebrew words, uniformly translated by veneficus or maleficus or witch, covered many different practitioners of the occult, from jugglers to astrologers. To refer to all of these different classes by one word (witch) was inadequate and erroneous. (2) The defination of witch based on the pact with Satan, transvection, metamorphosis, sabbat and maleficia was neither implied or defined anywhere in the Bible. That the Old Testament did not deal with witchcraft is hardly surprising, for witchcraft depended on a Christian demonology.

Thus Sir Walter Scott observed: It cannot be said that, in any part of that sacred volume [Old Testament], a text occurs indicating the existance of a system of witchcraft, under the Jewish dispensation, in any respect similar to that against which the law-books of so many European nations have, until very lately, denounced punishment. In the four Gospels, the word, under any sense, does not occur. (Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft) Lea suggested the biblical denunciations against sorcery were directed almost exclusively against divination. In fact, therefore, while it may discuss magic and occult customs, the Bible has nothing to do with heretical witchcraft.